Our improved model for gut microbiome dysbiosis

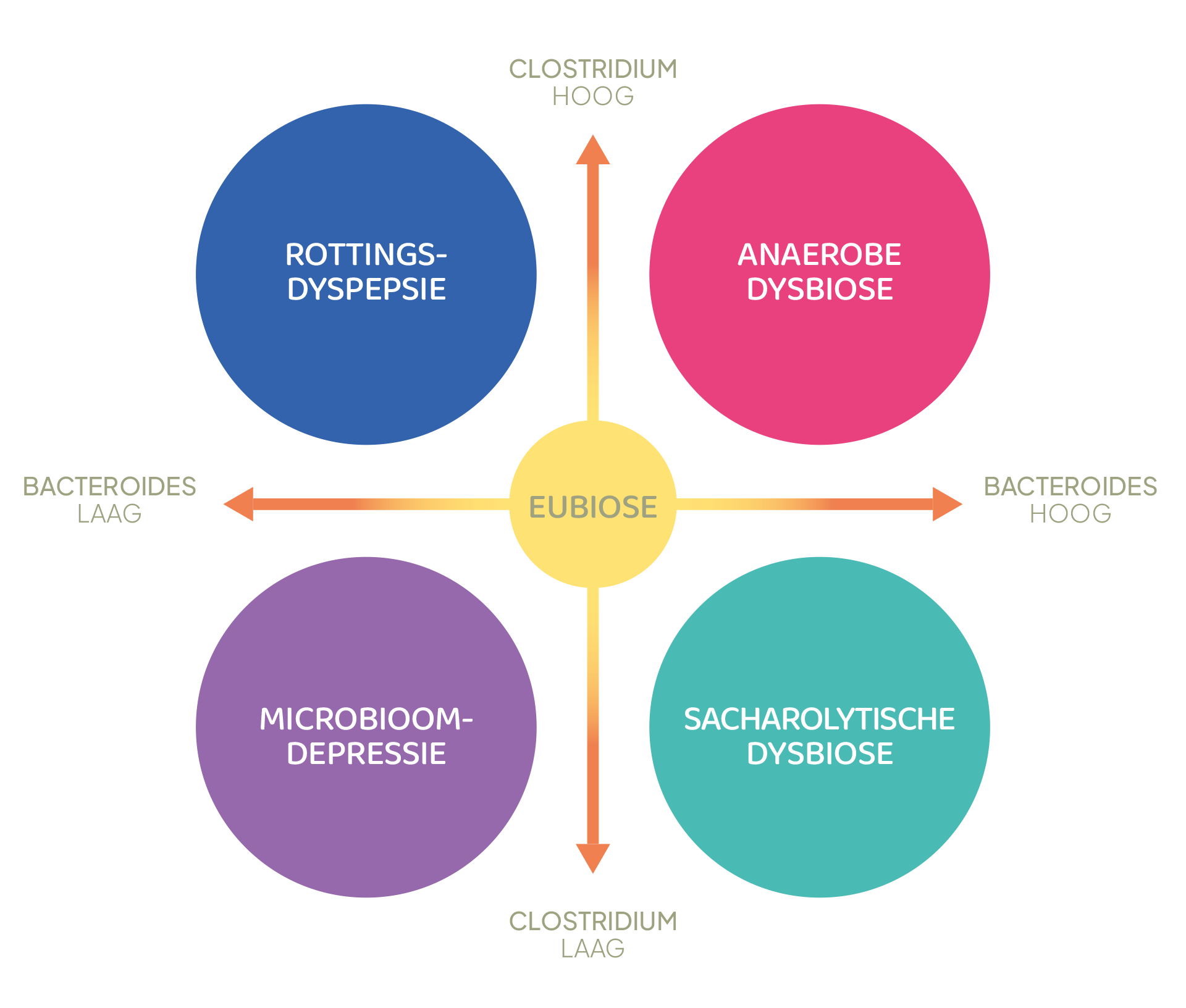

We believe the classical dysbiosis model is too limited and outdated, as it only considers two different states: balanced (eubiosis) and unbalanced (dysbiosis). Therefore, we have developed a more comprehensive and therefore more specific model. Our model recognizes four different basic types, each with its own characteristics and requiring its own approach. This provides the practitioner with a very useful and affordable diagnostic tool.

By Dr. Gijsbert J. Jansen , microbiologist at NL-Lab

What is Dysbiosis?

Dysbiosis is a disruption of a microbiome. If the situation is not disrupted, it is called eubiosis. In practice, the term eubiosis is rarely used, and the term dysbiosis is primarily associated with a disruption of the microbiological composition of the large intestine. When we talk about dysbiosis, we mean an imbalance of the gut microbiome.

Today, the relationship between dysbiosis and various conditions is well known and part of the medical-scientific literature [1].

The two main bacterial groups in the gut microbiome

The gut microbiome is a highly complex ecosystem composed primarily of vast numbers of bacteria. These can be divided into several groups. The two most important groups are Bacteroides and Clostridium .

The gut microbiome of an adult with a Western diet consists of approximately 80% of these two bacterial groups [ 2 ] . Deviations in the numbers and/or activity of these bacterial groups therefore determine the overall stability of the gut microbiome. For this reason, these groups form the basis of our dysbiosis model.

Four basic types of dysbiosis

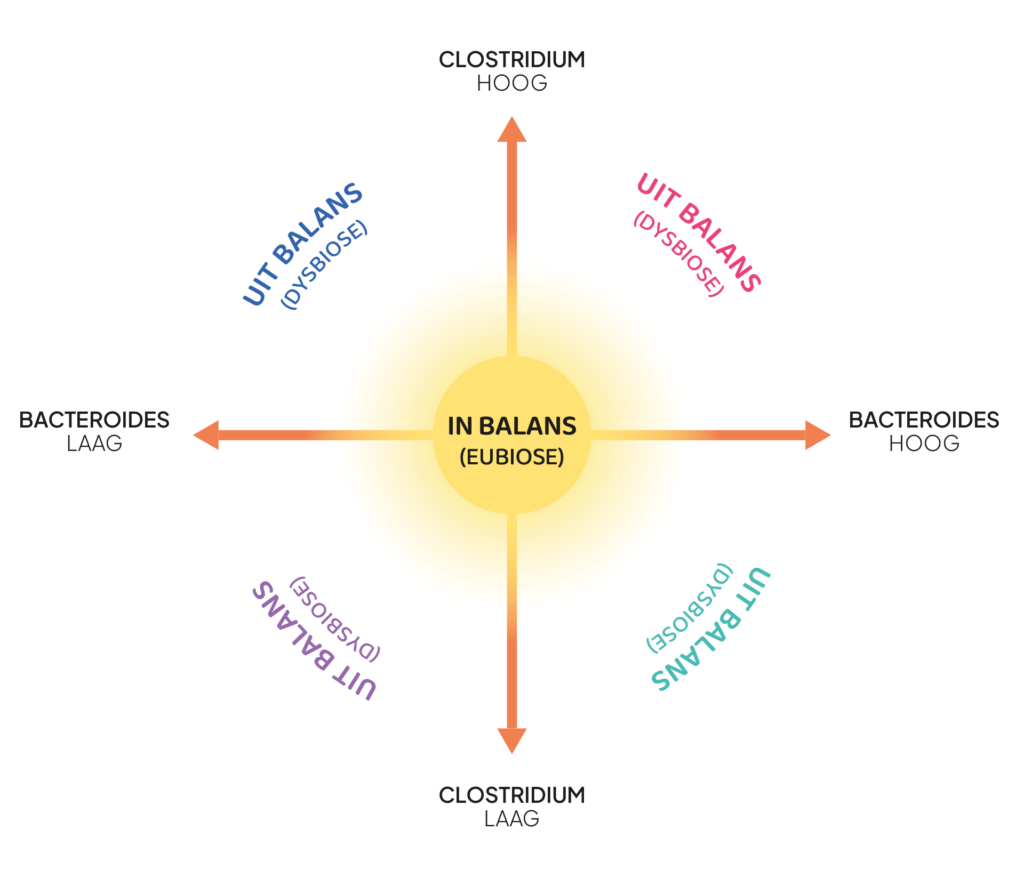

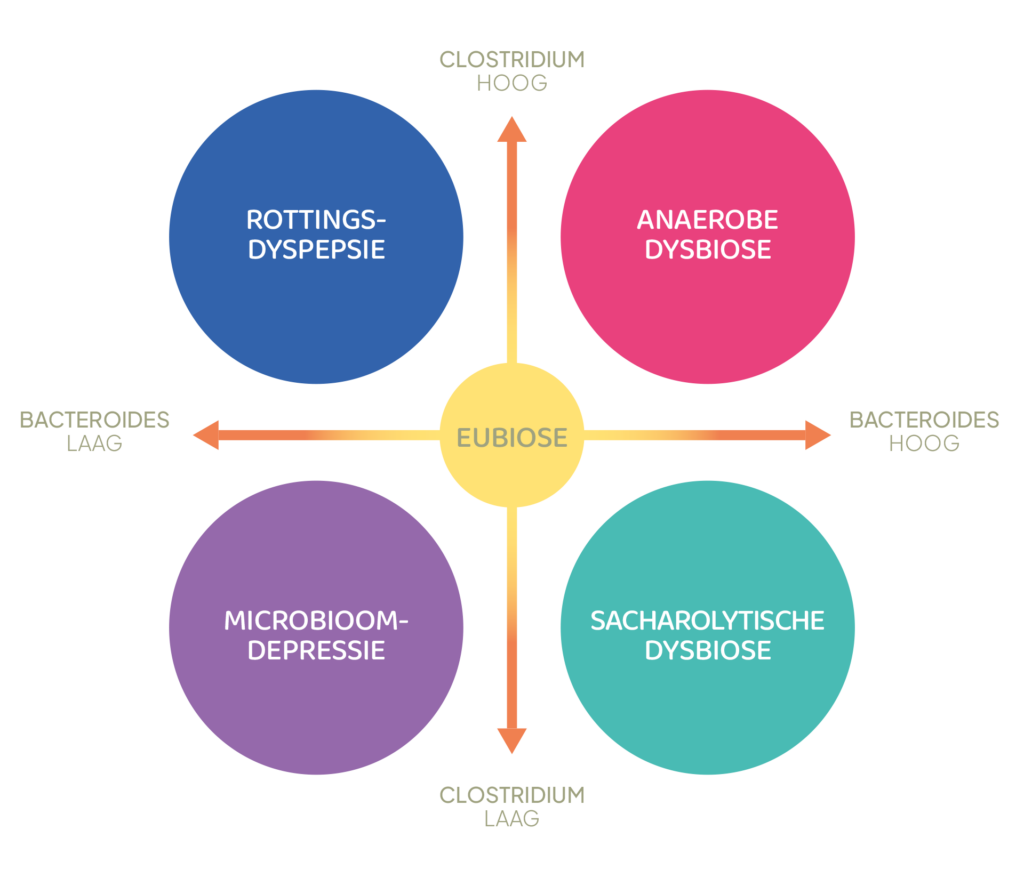

Since these groups can be either increased or decreased, a total of four types of dysbiosis are conceivable (Figures 1-2).

- Putrefactive dyspepsia (Clostridium high, Bacteroides low)

- Anaerobic dysbiosis (Clostridium high, Bacteroides high)

- Microbiome depression (Clostridium low, Bacteroides low)

- Saccharolytic dysbiosis (Clostridium low, Bacteroides high)

If one of the two bacterial groups is abnormal, this is called partial dysbiosis. The effect of partial dysbiosis is generally less severe than complete dysbiosis, in which the numbers of both Clostridia and Bacteroides are abnormal.

The type of dysbiosis is a first and important indicator to understand the status of the intestinal microbiome

Figure 1: Microbiome plot describing >80% of the gut microbiome

Figure 2: Definition of the four basic types of dysbioses

Relationship between dysbiosis and disorders

There are a number of direct physiological explanations for the dysbiotic type and its associated symptoms.

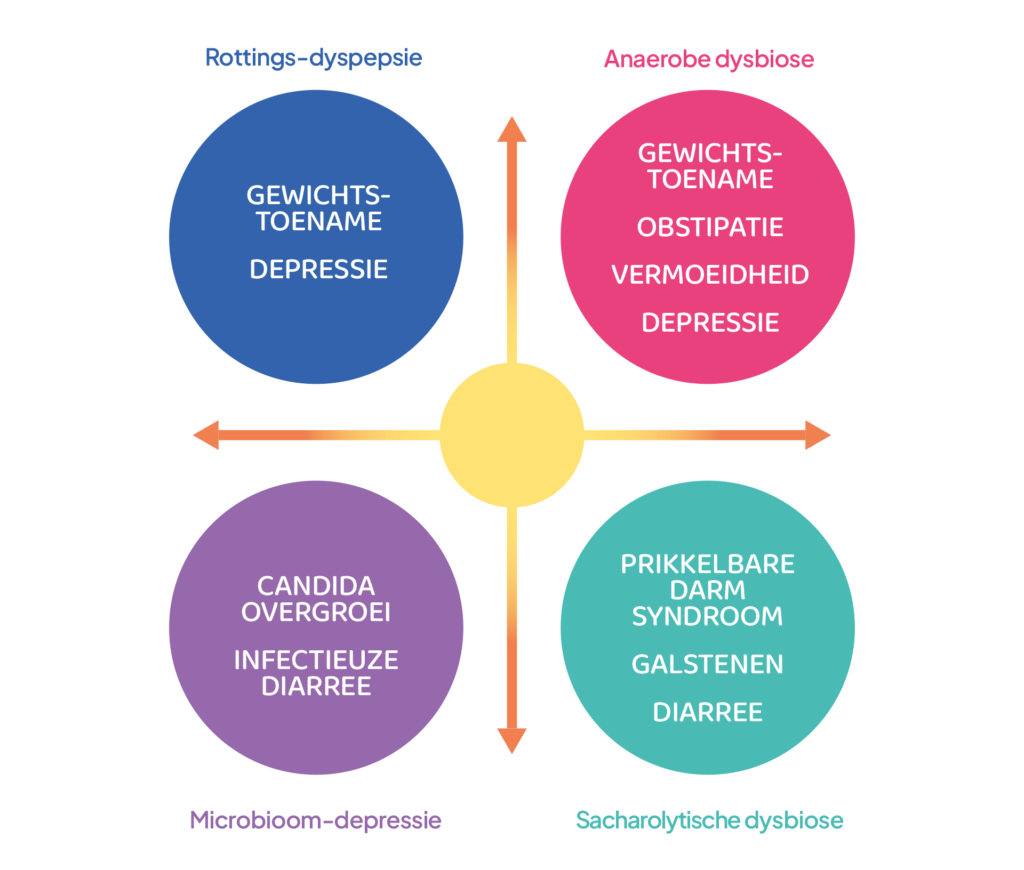

Figure 3 provides an indication of the potential health risks a patient is exposed to when experiencing one of the four possible types of dysbiosis. Naturally, these conditions have multiple causes beyond the dysbiotic status of the gut microbiome.

Figure 3: Symptom patterns associated with the four basic types of dysbiosis

Below, a brief explanation of cause and effect will be given for each dysbiotic situation.

Putrefactive dyspepsia

This is a dysbiotic situation in which Clostridium species dominate the microbiome. This type of dysbiosis is often associated with a typical Western diet with a relatively high proportion of fat and animal protein. The production of various neurotoxins also leads to depressive states and apathy [ 4 ] . As a result of the resulting reduction in physical activity, various secondary complaints can occur.

Anaerobic dysbiosis

This situation is a consequence of constipation . Intestinal contents stagnate, and the aerobic bacteria present "breathe" the oxygen until it is depleted. They then die from hypoxia ("suffocation"). The gut is now completely anaerobic, and the common anaerobes, including Bacteroides and Clostridia, increase in both numbers and microbial activity. Clostridia break down dietary protein and fat into neurotoxins, among other things, which can cause symptoms such as fatigue, loss of concentration, and depression . The slowed transit time allows the intestine more time to absorb fat before it comes into contact with the Clostridia in the large intestine. This can lead to weight gain .

Microbiome depression

This situation is a consequence of an excessively high intestinal transit rate . The reason for this increase can be multifactorial (antibiotic use is a common cause), but the consequences are fairly straightforward: because large areas of the intestinal ecosystem are now "uninhabited," pathogens from the outside world, via the oral route, can easily colonize the intestinal tract. Well-known examples are fungi and yeasts, such as Candida species. In addition, it is possible that pathogens (for example, via food) can enter the intestinal tract and subsequently cause an infection. Examples include Clostridioides difficile, Salmonella and Shigella species, and Listeria monocytogenes.

Sucharolytic dysbiosis

This is a dysbiotic condition in which Bacteroides species dominate the microbiome. Clostridia counts are usually low. As a result, Fusobacteria (originating from the oral microbiome) can establish themselves in the gut. This is an undesirable situation, as the prolonged presence of oral bacteria in the gut can lead to polyps and neoplastic tissue formation .

A second consequence of this type of dysbiosis is the overgrowth of Prevotella species . These species are often responsible for infectious colitis, small intestinal bowel overgrowth (SIBO), and arthritis. The (reduced numbers of) Clostridia produce enzymes that have pathological significance. One example is a decrease in 7α-dehydroxylating activity in the intestine, which significantly increases the risk of gallstones [ 5 ] .

How can you determine the type of dysbiosis?

If gut microbiome dysbiosis is suspected, a definitive diagnosis can only be made based on stool analysis. Traditional testing will only provide a dysbiosis index, meaning it remains unknown which type of dysbiosis you have.

The Pro Dysbiosis package for practitioners does provide all the necessary diagnostic information. In addition to the test results, you'll receive practical therapeutic advice tailored to the type of dysbiosis. A direct consequence of this is that the chance of therapeutic success will significantly increase. And all this at a very affordable price.

Individuals can order the Balance package in the webshop to gain insight into the type of dysbiosis.

Are you an individual interested in the Pro Dysbiosis package? You can contact us , and we'll send you a list of options from practitioners who offer this package.

Interested? Sign up!

The Pro Dysbiosis package can only be ordered by practitioners registered with us. After registering (without obligation), we will provide you with all relevant materials, including price lists.

References

- de Filippis, A., Ullah, H., Baldi, A., Dacrema, M., Esposito, C., Garzarella, E.U., Santarcangelo, C., Tantipongpiradet, A., & Daglia, M. (2020). Gastrointestinal Disorders and Metabolic Syndrome: Dysbiosis as a Key Link and Common Bioactive Dietary Components Useful for their Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(14), 4929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21144929

- Gacesa, R., Kurilshikov, A., Vich Vila, A., Sinha, T., Klaassen, MAY, Bolte, LA, Andreu-Sánchez, S., Chen, L., Collij, V., Hu, S., Dekens, JAM, Lenters, VC, Björk, JR, Swarte, JC, Swertz, MA, Jansen, BH, Gelderloos-Arends, J., Jankipersadsing, S., Hofker, M., … Weersma, RK (2022). Environmental factors shaping the gut microbiome in a Dutch population. Nature, 604(7907), 732–739. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04567-7

- de Vos, P., Garrity, G., & Jones, D. (2009). Systematic Bacteriology Second Edition Volume Three The Firmicutes: Vol. 3 Firmicutes (M. Goodfellow, P. Kampfer, P. de Vos, & F. Rainey, Eds.; 2nd ed.).

- Amirkhanzadeh Barandouzi, Z., Starkweather, A. R., Henderson, W. A., Gyamfi, A., & Cong, X. S. (2020). Altered composition of gut microbiota in depression: A systematic review. In Frontiers in Psychiatry (Vol. 11, pp. 1–10). Frontiers Media SA https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00541

- Wang, Q., Hao, C., Yao, W., Zhu, D., Lu, H., Li, L., Ma, B., Sun, B., Xue, D., & Zhang, W. (2020). Intestinal flora imbalance affects bile acid metabolism and is associated with gallstone formation. BMC Gastroenterology, 20(1), 59.

An earlier version of this article was published on the Natuurdietisten.nl website

To share:

Read also...