GJJansen, 2025

In psychology and psychotherapy, the brain is often approached as the primary point of contact for mood, motivation, and behavior. The gut-brain axis demonstrates that this approach is incomplete. The central nervous system does not function in isolation but is continuously connected to the gut through neural, hormonal, immunological, and metabolic pathways.

This mutual communication has direct consequences for processes that are relevant to healthcare providers on a daily basis.

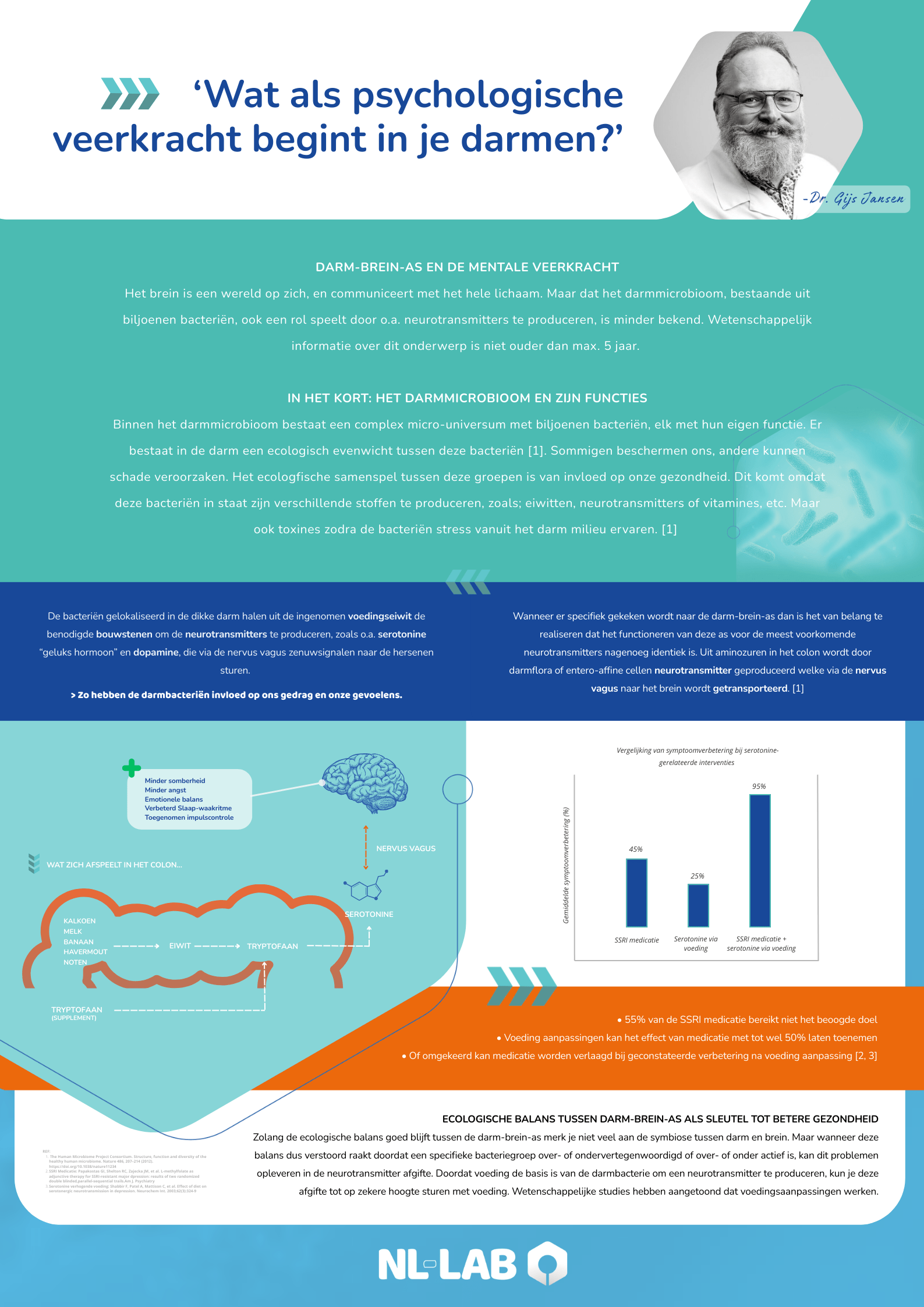

The role of the gut in neurotransmitter regulation

A major misconception is that neurotransmitters are produced exclusively "in the head." Take serotonin, for example. Approximately 90–95% of serotonin production occurs in the gut, largely under the influence of gut bacteria. Although this peripheral serotonin doesn't directly cross the blood-brain barrier, it does influence central serotonergic balance via the vagus nerve, immune pathways, and tryptophan availability. Changes in gut function or microbiome composition can therefore indirectly modulate mood, anxiety levels, and stress sensitivity.

Dopamine also fits into this framework. Dopamine is essential for motivation, reward, and goal-directed behavior, but it is biochemically dependent on amino acids like tyrosine and phenylalanine, which are found in all kinds of foods (yes, even chocolate!). The availability and metabolism of these amino acids are partly determined by the gut and its microbial population. Furthermore, inflammatory signals from the gut influence the dopaminergic circuits in the brain, with potential effects on anhedonia, mental fatigue, and concentration.

Interaction between gut microbiome, medication and treatment

These mechanisms provide insight into why oral medications can affect psychological functioning. Psychotropic drugs are partially metabolized by the gut microbiome, which can influence their efficacy and side effects. Conversely, antidepressants and antipsychotics can alter the composition and function of the microbiome, sometimes with metabolic or gastrointestinal consequences. Therefore, the effect of a drug is not only a matter of receptor binding in the brain, but also of its interaction with the gut ecosystem.

By the same token, it's understandable that nutritional interventions can be clinically relevant. Diet influences not only energy balance but also inflammatory activity, stress response, and the production of neuroactive metabolites. In practice, dietary adjustments are therefore increasingly used as part of lifestyle interventions and during medication tapering. During medication tapering, the nervous system is often more sensitive to fluctuations; nutritional support can contribute to greater physiological stability and less dysregulation.

For psychotherapists and psychologists, this doesn't replacing existing models, but rather significantly broadening them. Mental health issues arise and are maintained within an actively participating body. The gut-brain axis provides a biological framework that explains why combinations of psychotherapy, medication, and lifestyle are often more effective than a single intervention.

Interested or have questions?

NL-Lab experts are available to explain the above in more detail through video consultations or on-the-job training programs. For more information, please contact info@nl-lab.nl